Market Square Arena [Indianapolis]

Description: Former Stadium Location: 300 East Market Street, Indianapolis, IN Condition: Demolished Originally Photographed: July, 2001

A lonely traveler is driving his car on I-70 through Indianapolis on a sleepy Sunday morning just after dawn. Up ahead he notices roadblocks by several police cars with flashing lights. He slows to a stop, reaches for his coffee – and jumps to a loud explosion as a huge cloud of dust fills the sky. A bad truck accident? A train derailment? No, just the end of an Indiana original, Market Square Arena.

A lonely traveler is driving his car on I-70 through Indianapolis on a sleepy Sunday morning just after dawn. Up ahead he notices roadblocks by several police cars with flashing lights. He slows to a stop, reaches for his coffee – and jumps to a loud explosion as a huge cloud of dust fills the sky. A bad truck accident? A train derailment? No, just the end of an Indiana original, Market Square Arena.

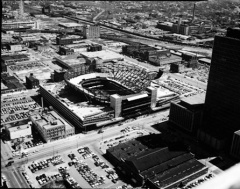

Market Square Arena in its glory days. There were large murals on the uprights – one showing an Indianapolis Ice player and another showing the great Pacer, Reggie Miller

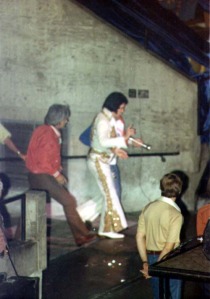

The city demolished MSA at 7:00 AM on July 8th, 2001. In that moment, the building that created thousands of memories – from graduations to high school basketball championships to lazy Saturdays spent with the Lipizzaner Stallions – was gone. MSA was where Elvis played his last concert before his death, where Wayne Gretzky first skated out on the ice to start his pro hockey career, and where Michael Jordan made his comeback from retirement in 1995. It was even the place where André the Giant defeated Hulk Hogan for the World Wrestling Federation title during the first televised wresting match since 1955. The facility, built by city fathers in 1974 for the now-paltry sum of $24 million, gave way to Conseco Fieldhouse (now Banker’s Life Fieldhouse), a $174 million palace for basketball. And basketball is really the story of MSA – one that runs deep into this hoop-happy state’s history.

Basketball wasn’t invented in Indiana – that honor goes to Springfield, MA where James A. Nasmith nailed a pair of peach baskets in 1891 to the wall at his YMCA and threw an old soccer ball out on to the floor. However, most believe that Indiana perfected the game: Rev. Nicholas McKay brought it to his Crawfordsville YMCA in 1894 and had a blacksmith create a pair of metal hoops to hang on the wall to make the ball easier to retrieve. In 1925, James Nasmith himself visited the state finals game that year and wrote, “Basketball really had its origin in Indiana, which remains the center of the sport.”

Despite this history, though, in 1967 there was no major league professional team playing in Indiana. There had been a few in the past – including the Zollner Pistons who played in Fort Wayne between 1941 and 1957 before moving to Detroit to become the Detroit Pistons. A few civic and business leaders got together to buy a franchise in the new American Basketball Association – a league that was a response to the slow expansion of the NBA in the 1960s. It was felt that rather than waiting for the NBA to expand, a separate league might be able to force an expansion into markets that could clearly support a professional team. They named the team “Indiana Pacers”, the “Indiana” in the hopes of drawing more support than from just Indianapolis, and “Pacers” from the pace car in a race.

The early years were rough – players played games in the drafty old coliseum at the Indiana State Fairgrounds, lightly booked since a catastrophic gas explosion that damaged the building and killed 74 people near the end of a Holiday On Ice performance on October 31, 1963. The teams really didn’t have decent locker rooms, but the crowds were good and the team ended the first year with a decent 38-40 record.

Program from the famous ABA vs. NBA All-Stars game in 1971. The NBA beat the ABA team 125 to 120. NBA rules governed the first half and ABA rules the second. [Click for a larger picture.]

It was in this environment that the ABA powerhouse began to find its surroundings somewhat inadequate. Indianapolis was a small town trying to become a city – many called it “Naptown” or “India-no-place”. Mayor Richard Lugar, who would eventually become a senator from Indiana, realized that the Pacers were just the sort of thing that the city needed to keep. The problems were huge, however: the city’s downtown was dying due to suburban flight, so leaders wanted to find a way to put the arena there to stimulate commerce rather than the spot the Pacers had picked out on the growing northwest quadrant of the city. However, buying land and demolishing buildings would add millions to the cost of a project that the small city wasn’t sure how it was going to pay for in the first place.

Out of these problems would be born a unique civic-private partnership that would become the model for future projects in Indianapolis as well as other cities. On April 12, 1971, Mayor Lugar announced that a new 18,000 seat multipurpose arena would be built, including two 12-story office buildings and three parking garages. In order to get around the land problem, a parking garage would be built both on the north and the south sides of Market Street west of Alabama Street, and the arena would be built on top of the garages, straddling Market Street, which would run under the building! The city would fund 1/3 of the original $32 million price tag, with the balance paid for by a private investor group backed by Fred Tucker, an Indianapolis realtor and J. Fred Risk, president of Indiana National Bank. The city bought the two small plots of land, the investor group, named “Market Square Associates” would construct the garages, and the city would build the arena on top of them. Market Square Associates would then lease the arena from the city and run it on behalf of the Pacers.

A little known fact is that this creative solution was actually devised by two Ball State University students, Joseph Mynheir and Terry Pastorino as an architectural class project in November, 1970. General contractor Huber, Hunt & Nichols (who would go on to build Cleveland Browns stadium, Pacific Bell Park in San Francisco, and the new Conseco Fieldhouse in Indianapolis, among others) would take the plans and build the stadium. Groundbreaking occurred on October 20, 1971. Construction would take almost 2 years, with the first event, a Glen Campbell concert, held on September 15, 1974. The first regular-season ABA game was held on October 18, 1974 against the San Antonio Spurs, which the Pacers lost in overtime, 129-121. Interestingly that game only drew 7,473, while the first basketball game ever held in the arena – a preseason game against the Milwaukee Bucks – drew 16,929.

Alas, the days of the ABA were running short. The Pacers began to have financial troubles like most of the other teams in the league. They could no longer hold on to key players, like George McGinnis (another league co-MVP with Julius Erving) who left for the NBA. Most of the original owners had anticipated an early merger, not a protracted battle, and they simply began to run out of money. During the summer of 1976 the four strongest teams – the Pacers, the Denver Nuggets, the San Antonio Spurs and the New York Nets – would join the NBA – by each paying $3.2 million fee. The other ABA teams died, unable to pay this tribute. The New York Nets (who would become the New Jersey Nets) paid an extra $4 million directly to the New York Knicks as penalty for lost revenue. A fifth team, the St. Louis Spirits, failed to make the league, but in tribute the other four teams pay 1/7th of their TV revenues to the former Spirits owners forever. Many of the rules that made the ABA so exciting would also join the NBA, including the 30-second shot clock and the 3-point line. Market Square Arena would continue as the Pacers’ home in the NBA.

Many memorable events occurred in the building in the following decades, including the last concert of one Elvis Aaron Presley, held on June 26th, 1977 in front of over 18,000 people. He would die in the early morning on August 16, 1977.

Ironically, many of the features that made the building unique would eventually prove its undoing. Since the building was literally perched above a city street, there was only one small loading ramp on the back of the building. Trucks setting up for a concert could only come up the ramp one at a time, and then there was no real place for them to park while the show was on. The city took to carefully parking them on Market Street’s median, under the building, bumper to bumper. The building was extremely steep with narrow paths through the stands – ask anyone who tried to walk down the steps why so many would lose their orientation and fall. The last blow came when Pacers’ management deemed the stadium unable to support the new private boxes which have become a major new revenue stream for NBA teams. Instead, the same public/private partnership would build a new crown jewel – Conseco Fieldhouse – in the shadow of the old arena. The last Pacer game was held on October 23, 1999 – a pre-season exhibition game against the Utah Jazz – a team who themselves owe their existence to the ABA Utah Stars who proved a smaller market could support a professional basketball team. Coach Larry Bird handed Bobby “Slick” Leonard, the man most associated with the Pacer’s ABA days, a ball at the end of the last practice. Bobby sunk the shot – and thereby made the very first and the very last baskets at MSA.

Though perhaps unsuitable for basketball, it seemed to most that another use for the building could be found. Citizens attending a public hearing in September, 1999 opposed the demolition 3 to 1. In fact, concerts and special shows had been held in the building for years, and many felt it could be converted into a full-time hockey arena for the Indianapolis Ice. Unfortunately, none of the ideas also came along with funding – it cost the city over $1 million per year simply to heat the building, and its nearly 30-year-old escalators and air conditioning equipment were in need of replacement. On November 22nd, 1999, just one month after the last event, the city announced it would seek bids to demolish the building and turn the spot into two parking lots – with Market Street still running through the middle.

Work began in April, 2001 as the wrecking ball removed the most of the parking garages on which the arena sits. By demolition day, workers had cut most of he roof away, exposing the open beams that supported the dome. On May 14th, workers accidentally started a small fire when they didn’t realize the roof material had paper insulation on it’s back. The city contracted Controlled Demolition of Baltimore, MD, a world-renown firm, to implode the main structure. All throughout June of 2001 the building’s structure was strategically weakened, and workers wired 800 pounds of explosives to a central command post. In the days before the event, thick black curtains were hung down from the buildings surrounding the site to protect nearby windows from debris. Drapes completely covered one small bail bond building only a few hundred feet away. The curtains almost made the buildings appear as if they were in mourning.

At 5:30 AM on Sunday, July 8th, 2001, police began to enforce a “safety zone” around the building, designed to protect onlookers and discourage people from showing up for fear of being too far away to see anything. Unlike other cities who have thrown large parties surrounding demolition of large buildings, Indianapolis chose to downplay the event. Reportedly aides had to persuade the mayor even attend. At 6:45 AM police shut off all I-65 and I-70 leading into and out of downtown – it was felt that traffic traveling on these roads early on a Sunday morning would be dangerously surprised by an arena imploding a few hundred yards away.

The end came in only 12 seconds. At precisely 7:00 AM, Controlled Demolition set off a series of loud bangs – blasting caps that started chain-reaction explosions. One large explosion followed which started the roof dome collapse, and a second smaller explosion cut the steel support ring around the building into neat pieces. Only seven windows smashed in the buildings next door, replaced the very same day. By that afternoon, the streets were clear of hundreds of pounds of dust and paper board insulation.

One of the trickiest parts of the demolition required that workers be able to reach a utility panel for the east side of downtown under the arena, so CDI expertly kept the bridge intact – still supporting an arena floor piled with millions of pounds of concrete and twisted metal.

Metal that is now gone, leaving only two gravel parking lots, many memories, and another marker of Lost Indiana.

One of the local TV stations in Indianapolis placed a media pool camera inside of the building to capture its collapse. This is astonishing video of a unique moment.

On a brighter note, in February 2008, New Line Cinema released a comedy movie set in 1976 related to the ABA. Semi-Pro featured Will Ferrell as the leader of the fictional ABA Flint Tropics. At one point in the movie he visits Indianapolis to discuss the future of his franchise with officials of the ABA. In the conference room where the meeting occurs (set at Market Square Arena) there are pictures of the Pacers and of MSA – all from this website. 🙂 Buy it from Amazon.com.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “Market Square Arena [Indianapolis],” an entry on Lost Indiana

- Published:

- July 8, 2001 / 12:01 pm

- Category:

- Premier Privation

- Tags:

- ABA, Basketball, Elvis, Lost Indiana, nba, Urban Ruins

11 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]